Confrontations

Entrer:

Published by Wallonie- Bruxelles Architectures

2015

ISBN: 9782930705132

Confrontations

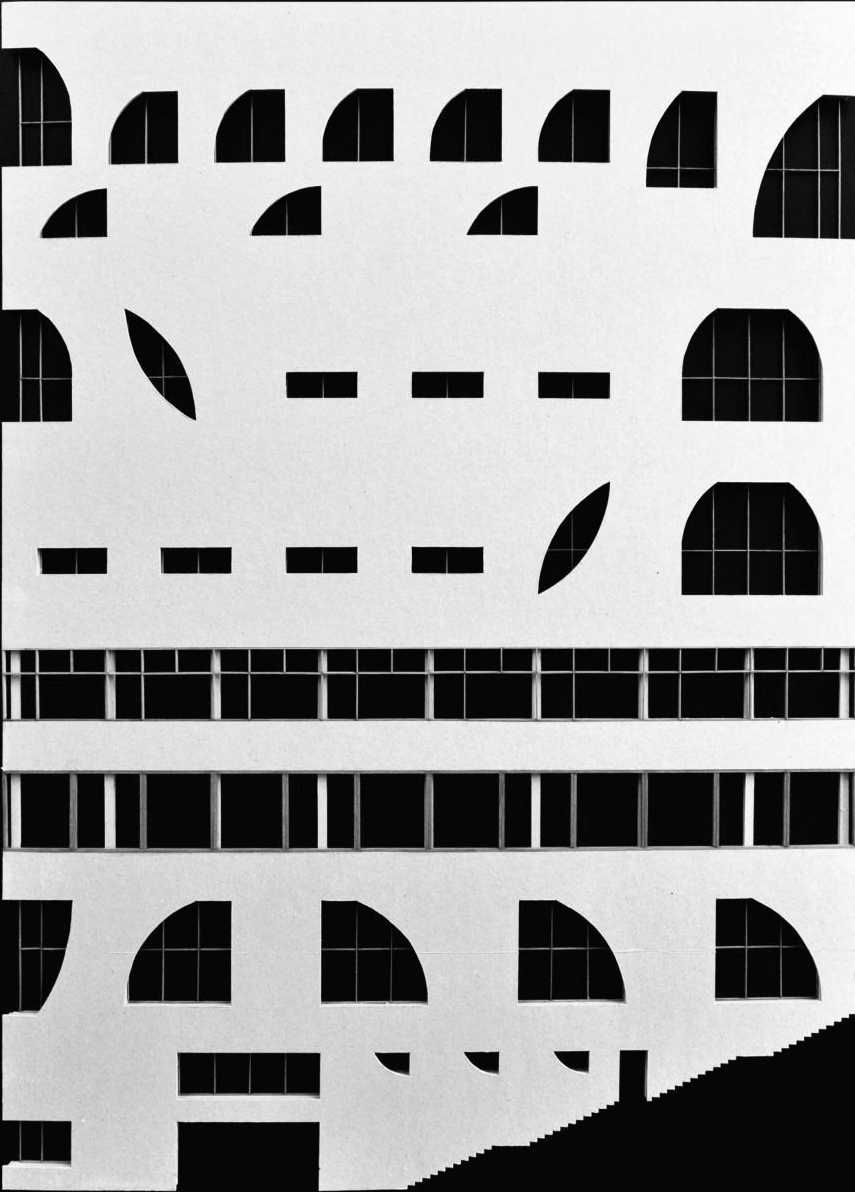

''In 1952 German architect Hans Döllgast was commissioned to renovate the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. Originally designed by Leo von Klenze in 1836 as the largest art museum of its time, it was heavily damaged by bombing in World War II. Döllgast refused to repair the edifice as expected from a classic restoration. His aim was to emphasise the importance of history without compromising: parts of the destroyed facade had to remain visible, a goal achieved by rebuilding them in brickwork alone and by omitting the finishing of the ochre-coloured plaster and the embellishments of the original facade. Through this simple yet stubborn gesture, the confrontation with history became so conspicuous that still today this building remains a striking object of study. Without much explanation one grasps, or imagines, that something happened to the building, something destructive that should not be forgotten. Döllgast’s approach to monument preservation was controversial in its day but became widely appreciated over time. In the interior the architect kept up the provocative principle used outside and kept the walls barren where necessary, functionally restoring the grand staircase leading from the vestibule to the exhibition halls on the upper floor. Parting in two directions parallel to the outer facade, this staircase causes an inner elevation as well. The visitor moves between the two sober brick fronts before entering von Klenze’s neoclassicist enfilade.

In converting the Ursulines convent into a place to show and conserve the local heritage of Mons, the Brussels-based architectural practice L’escaut did not have to deal with the same weight of history as Döllgast in the Alte Pinakothek. Though part of the complex was also bombed during WWII, L’escaut’s assignment from 2013 for the conversion is situated directly in the chapel, which carried the traces of its age. The question of the approach to monument preservation, raised by Döllgast 60 years ago, is equally relevant here. In the Ursulines convent the architects were inevitably confronted with the decay of a 350-year-old building that evidently underwent some renovation for its survival. But in 2013 the building needed a radical rethink because of its programmatic change into a public storage place for the municipal heritage of Mons. In architecture there has been a growing tendency to keep parts of the original construction of an existing building. It is for instance discernible in such subtle renovations as Tate Britain by Caruso & St John (completed in 2010) without touching the original and adding some silent contemporary elements most visible in the rotunda, or in the direct confrontation with history which David Chipperfield Architects opted for in the Neues Museum project in Berlin (completed in 2009). ''